The most widely-used standard we have for color reproduction on video equipment is the sRGB standard. You might think you have excellent color reproduction on your monitor or TV, but the purpose of this post is to convince you otherwise.

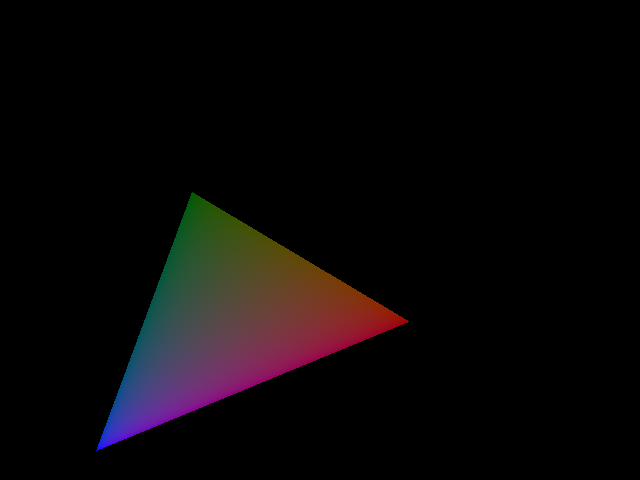

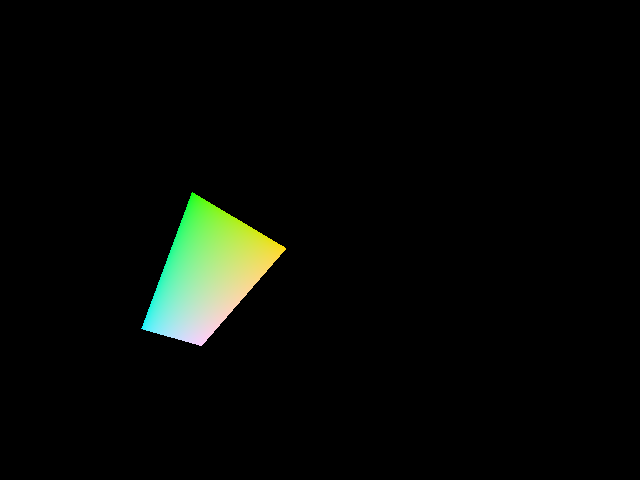

At low brightness levels, sRGB does a decent job of reproducing the great variety of colors that the human eye can perceive. At brightness levels up to 7.2%, the entire range of hues spanned by the sRGB primary colors is available for display. This rendering shows that palette in CIE 1931 (x,y) coordinates:

Unfortunately, we have a problem. The above triangle appears to have uniform brightness, right? At least, it does according to the CIE 1931 color perception model. Now, see that blue corner in the lower left? We have sadly maxed out your monitor's ability to display blue. If you use 24-bit color, then the RGB values for that corner are (0, 0, 255). This is an unfortunate fact of human perception: blue just doesn't appear very bright, even when the number of photons reaching your eye is large.

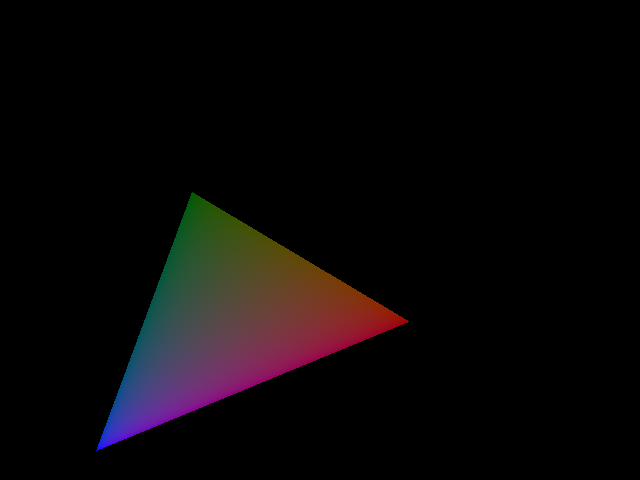

If we want to go brighter than this, we have to start compromising. The full range of hues will no longer be available to us, because we'll have to start turning on red and green, even if the color we want to display is blue. As we increase the perceived brightness above 7.2%, we lose progressively more of the sRGB color gamut, until we reach the intensity of a bright red pixel:

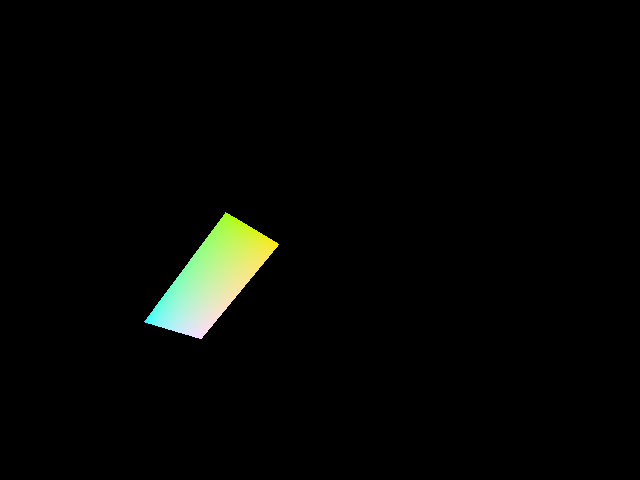

There we go. Now we're at a brightness level of 21.3% — but we can no longer display a deeply saturated blue. A little chunk of the sRGB gamut has gone missing. At this point, the right corner is full intensity red, without any green or blue. If we want to go brighter yet, we'll have to start clipping the red corner as well:

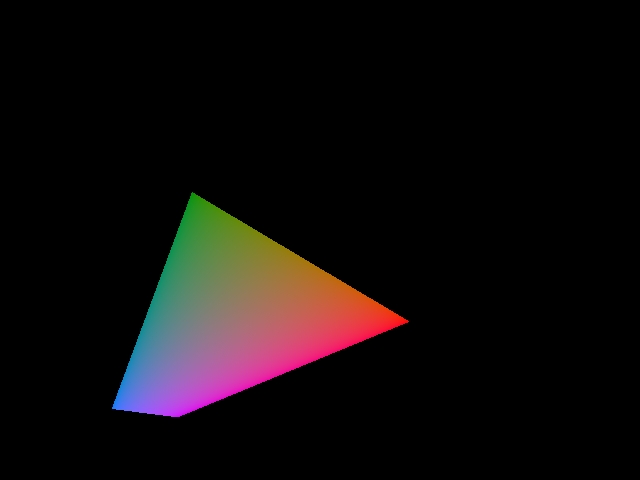

Now we're at a brightness level of 28.5%. There are no more fully-saturated reds or blues, and the magenta vertex is now maxed out. If we continue turning up brightness, we lose our ability to display fully-saturated purples. As we increase brightness further, the sRGB gamut continues to shrink, but at least we can still display a fully saturated green. This situation continues for quite some time, until we reach a perceived brightness of 71.5%:

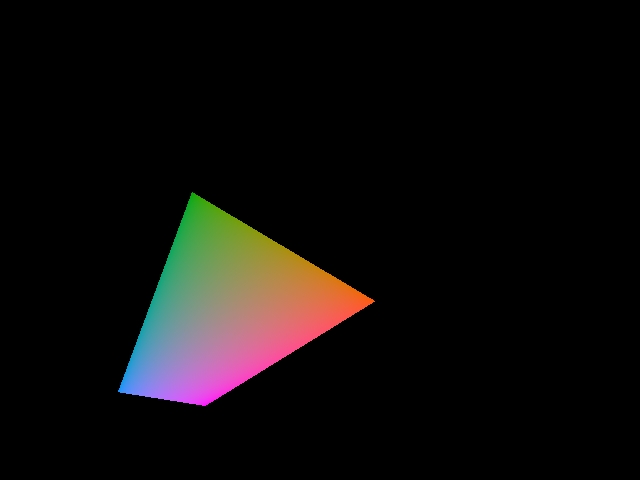

At this brightness, first blue, then red, then magenta have been clipped away to oblivion. If we go brighter yet, we have to start clipping green, because the top pixel of the remaining quadrilateral is full-on green. Continuing to 78.7% brightness reduces our gamut even further:

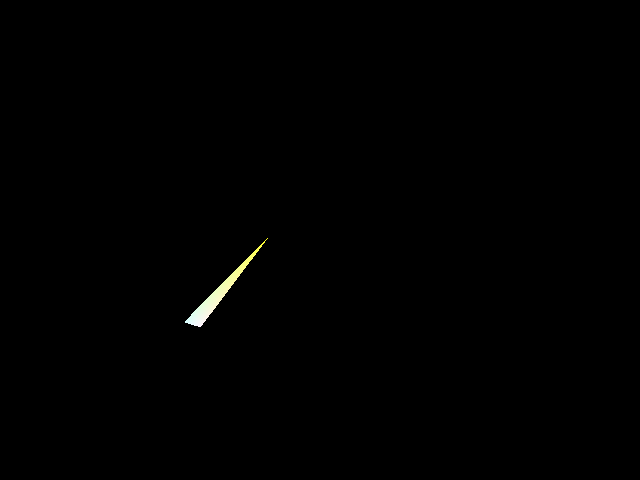

All that\'s left is cyan and yellow — there are no more fully saturated primary colors. As we proceed above 78.7% brightness, cyan gets clipped as well, until, at 92.8% brightness, all that's left is yellow and white:

What a sad color gamut this is! Yet, if you want to display a color with a very high percentage of your monitor's maximum brightness, this tiny little sliver of a triangle tells you what you have to work with. Yellow and white. That's all.

To be fair, this shrinkage of color gamut as perceived intensity increases isn't really sRGB's fault. The human eye, with its asymmetric perception of color and brightness, is largely to blame. Blue is dark. Red isn't all that bright. Much of perceived brightness comes from the green wavelengths. Even so, I was shocked to see just how much this color gamut shrinks even at modest brightness levels.